The following comes from William Noyes’s 1910 classic, Handwork in Wood. See also “Handwork in Wood” – Wood Hand Tools Part One: Traditional Cutting Tool Concepts and “Handwork in Wood” – Wood Hand Tools Part Two: Chisels.

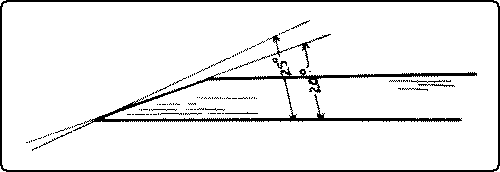

In sharpening a chisel it is of first importance that the back be kept perfectly flat. The bevel is first ground on the grindstone to an angle of about 20° and great care should be taken to keep the edge straight and at right angles to the sides of the blade.

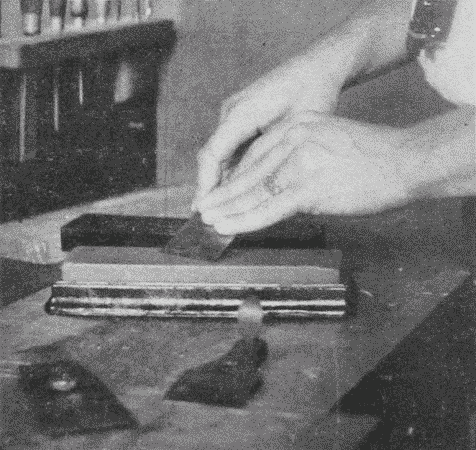

After grinding it is necessary to whet the chisel and other edged tools. First see that there is plenty of oil on the stone. If an iron box be used, Fig. 77, the oil is obtained simply by turning the stone over, for it rests on a pad of felt which is kept wet with kerosene.

Place the beveled edge flat on the stone, feeling to see if it does lie flat, then tip up the chisel and rub it at an angle slightly more obtuse than that which it was ground, Fig. 78. The more nearly the chisel can be whetted at the angle at which it was ground the better. In rubbing, use as much of the stone as possible, so as to wear it down evenly. The motion may be back and forth or spiral, but in either case it should be steady and not rocking. This whetting turns a light wire edge over on the flat side. In order to remove this wire edge, the back of the chisel, that is, the straight, unbeveled side, is held perfectly flat on the whetstone and rubbed, then it is turned over and the bevel rubbed again on the stone. It is necessary to reverse the chisel in this way a number of times, in order to remove the wire edge, but the chisel should never be tipped so as to put any bevel at all on its flat side. Finally, the edge is touched up (stropped) by being drawn over a piece of leather a few times, first on one side, then on the other, still continuing to hold the chisel so as to keep the bevel perfect.

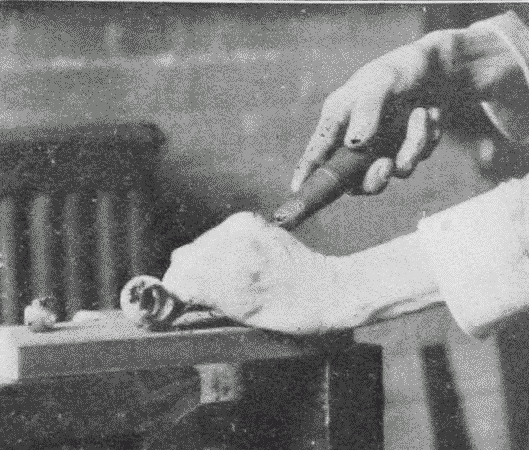

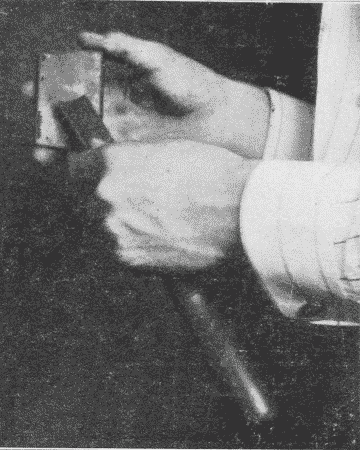

To test the sharpness of a whetted edge, draw the tip of the finger or thumb lightly along it, Fig. 79. If the edge be dull, it will feel smooth: if it be sharp, and if care be taken, it will score the skin a little, not enough to cut thru, but just enough to be felt.

(Want to see chisel sharpening in action? Check out our online sharpening course, especially our free chisel sharpening video.)

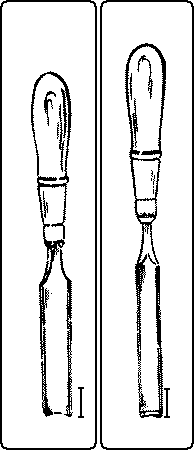

The gouge is a form of chisel, the blade of which is concave, and hence the edge curved. When the bevel is on the outside, the common form, it is called an outside bevel gouge or simply a “gouge,” Fig. 80; if the bevel is on the inside, it is called an inside bevel, or inside ground, or scribing-gouge, or paring-gouge, Fig. 81.3

Footnote 3: Another confusing nomenclature (Goss) gives the name “inside gouges” to those with the cutting edge on the inside, and “outside gouges” to those with the cutting edge on the outside.

Carving tools are, properly speaking, all chisels, and are of different shapes for facility in carving.

For ordinary gouging, Fig. 82, the blade is gripped firmly by the left hand with the knuckles up, so that a strong control can be exerted over it. The gouge is manipulated in much the same way as the chisel, and like the chisel it is used longitudinally, laterally, and transversely.

In working with the grain, by twisting the blade on its axis as it moves forward, delicate paring cuts may be made. This is particularly necessary in working cross-grained wood, and is a good illustration of the advantage of the sliding cut.

In gouging out broad surfaces like trays or saddle seats it will be found of great advantage to work laterally, that is across the surface, especially in even grained woods as sweet gum. The tool is not so likely to slip off and run in as when working with the grain.

The gouge that is commonly used for cutting concave outlines on end grain, is the inside bevel gouge. Like the chisel in cutting convex outlines, it is pushed or driven perpendicularly thru the wood laid flat on a cutting board on the bench, as in perpendicular chiseling, Fig. 72.

In sharpening an outside bevel gouge, the main bevel is obtained on the grindstone, care being taken to keep the gouge rocking on its axis, so as to get an even curve. It is then whetted on the flat side of a slipstone, Fig. 83, the bevel already obtained on the grindstone being made slightly more obtuse at the edge. A good method is to rock the gouge on its axis with the left hand, while the slipstone held in the right hand is rubbed back and forth on the edge. Then the concave side is rubbed on the round edge of the slipstone, care being taken to avoid putting a bevel on it. Inside bevel gouges need to be ground on a carborundum or other revolving stone having a round edge. The outfit of the agacite grinder, contains one of these stones. The whetting, of course, is the reverse of that on the outside bevel gouge.

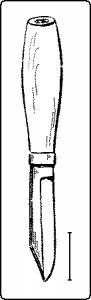

The knife differs from the chisel in two respects, (1) the edge is along the side instead of the end, and (2) it has a two-beveled edge. Knives are sometimes made with one side flat for certain kinds of paring work, but these are uncommon. The two-beveled edge is an advantage to the worker in enabling him to cut into the wood at any angle, but it is a disadvantage in that it is incapable of making flat surfaces. The knife is particularly valuable in woodwork for scoring and for certain emergencies. The sloyd knife, Fig. 84, is a tool likely to be misused in the hands of small children, but when sharp and in strong hands, has many valuable uses. A convenient size has a 2½ inch blade. When grinding and whetting a knife, the fact that both sides are beveled alike should be kept in mind.

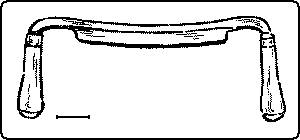

The draw-knife, Fig. 85, is ground like a chisel, with the bevel only on one side, but the edge is along the side like a knife. Instead of being pushed into the wood, like a chisel, it is drawn into it by the handles which project in advance of the cutting edge. The handles are sometimes made to fold over the edge, and thus protect it when not in use. The size is indicated by the length of the cutting edge. It is particularly useful in reducing narrow surfaces and in slicing off large pieces, but it is liable to split rather than cut the wood.

(You can see the gouge, drawknife and knife all at work in our online From a Log to a Spoon course.)

Noyes, W. (1910). Chapter IV. WOOD HAND TOOLS. In Handwork in Wood (pp. 54-59). Peoria, Ill.: Manual Arts Press

Learn all about chisels and more online here at the Heritage School of Woodworking’s Online Woodworking Courses, especially the free How to Sharpen a Chisel video. Be sure to check out the Basics of Joinery course; it’s got lots of chiseling! This blog is also relevant to this article: How to Sharpen a Chisel blog.

Comments are closed.