The following comes from William Noyes’s 1910 classic, Handwork in Wood. See the whole Handwork in Wood series (so far) here. More to come.

Chopping Tools

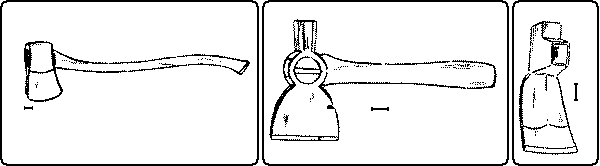

The primitive “chopping tool”, which was hardly more than a wedge, has been differentiated into three modern hand tools, the chisel…the ax, Fig. 139, and the adze, Fig. 141.

The ax has also been differentiated into the hatchet, with a short handle, for use with one hand, while the ax-handle is long, for use with two hands. Its shape is an adaption to its manner of use. It is oval in order to be strongest in the direction of the blow and also in order that the axman may feel and guide the direction of the blade. The curve at the end is to avoid the awkward raising of the left hand at the moment of striking the blow, and the knob keeps it from slipping thru the hand. In both ax and hatchet there is a two-beveled edge. This is for the sake of facility in cutting into the wood at any angle.

There are two principal forms, the common ax and the two bitted ax, the latter used chiefly in lumbering. There is also a wedge-shaped ax for splitting wood. As among all tools, there is among axes a great variety for special uses.

| Fig. 139. Ax. | Fig. 140. Shingling Hatchet. | Fig. 141. Carpenter’s Adze. |

The hatchet has, beside the cutting edge, a head for driving nails, and a notch for drawing them, thus combining three tools in one. The shingling hatchet, Fig. 140, is a type of this.

The adze, the carpenter’s house adze, Fig. 141, is flat on the lower side, since its use is for straightening surfaces.

Scraping Tools

Scraping tools are of such nature that they can only abrade or smooth surfaces.

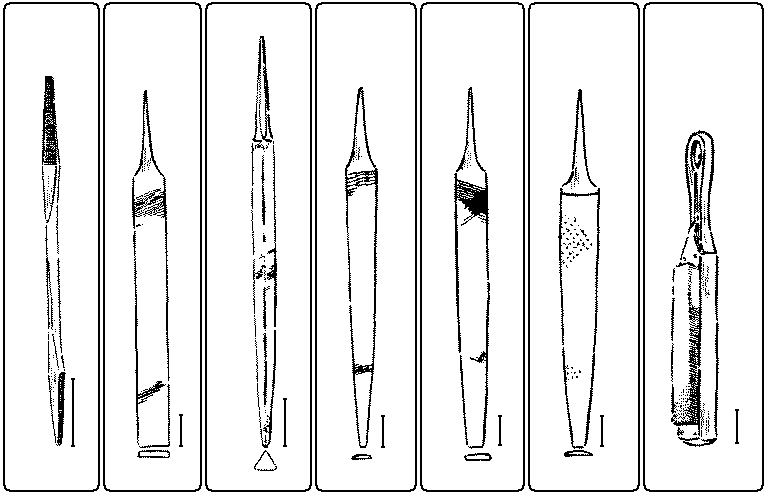

| 142 | 143 | 144 | 145 | 146 | 147 | 148 |

| Fig. 142. Auger-Bit-File. Fig. 143. Single-Cut Blunt, Flat, Bastard File. Fig. 144. Three-Square Single-Cut File. Fig. 145. Open Cut, Taper, Half-Round File. Fig. 146. Double-Cut File. Fig. 147. Cabinet Wood-Rasp. Fig. 148. File-Card. |

Files. Figs. 142-146, are formed with a series of cutting edges or teeth. These teeth are cut when the metal is soft and cold and then the tool is hardened. There are in use at least three thousand varieties of files, each of which is adapted to its particular purpose. Lengths are measured from point to heel exclusive of the tang. They are classified: (1) according to their outlines into blunt, (i. e., having a uniform cross section thru out), and taper; (2) according to the shape of their cross-section, into flat, square, three-square or triangular, knife, round or rat-tail, half-round, etc.; (3) according to the manner of their serrations, into single cut or “float” (having single, unbroken, parallel, chisel cuts across the surface), double-cut, (having two sets of chisel cuts crossing each other obliquely,) open cut, (having series of parallel cuts, slightly staggered,) and safe edge, (or side,) having one or more uncut surfaces; and (4) according to the fineness of the cut, as rough, bastard, second cut, smooth, and dead smooth. The “mill file,” a very common form, is a flat, tapered, single-cut file.

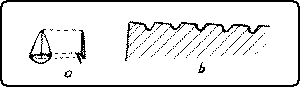

Rasps, Fig. 147, differ from files in that instead of having cutting teeth made by lines, coarse projections are made by making indentations with a triangular point when the iron is soft. The difference between files and rasps is clearly shown in Fig. 149.

It is a good rule that files and rasps are to be used on wood only as a last resort, when no cutting tool will serve. Great care must be taken to file flat, not letting the tool rock. It is better to file only on the forward stroke, for that is the way the teeth are made to cut, and a flatter surface is more likely to be obtained.

Both files and rasps can be cleaned with a file-card, Fig. 148. They are sometimes sharpened with a sandblast, but ordinarily when dull are discarded.

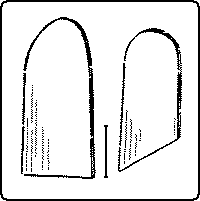

Scrapers are thin, flat pieces of steel. They may be rectangular, or some of the edges may be curved. For scraping hollow surfaces curved scrapers of various shapes are necessary. Convenient shapes are shown in Fig. 150. The cutting power of scrapers depends upon the delicate burr or feather along their edges. When properly sharpened they take off not dust but fine shavings. Scrapers are particularly useful in smoothing cross-grained pieces of wood, and in cleaning off glue, old varnish, etc.

There are various devices for holding scrapers in frames or handles, such as the scraper-plane, Fig. 111, p. 79, the veneer-scraper, and box-scrapers. The veneer-scraper, Fig. 151, has the advantage that the blade may be sprung to a slight curve by a thumb-screw in the middle of the back, just as an ordinary scraper is when held in the hands.

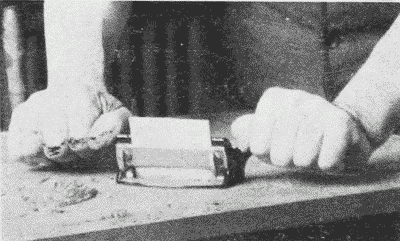

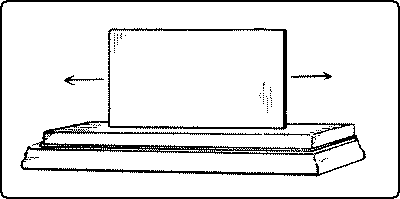

In use, Fig. 152, the scraper may be either pushed or pulled. When pushed, the scraper is held firmly in both hands, the fingers on the forward and the thumbs on the back side. It is tilted forward, away from the operator, far enough so that it will not chatter and is bowed back slightly, by pressure of the thumbs, so that there is no risk of the corners digging in. When pulled the position is reversed.

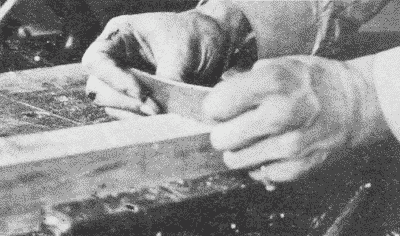

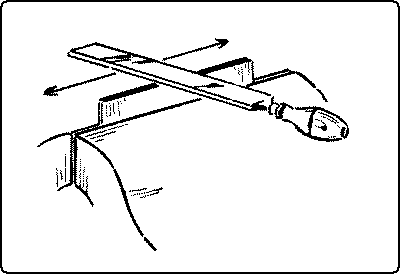

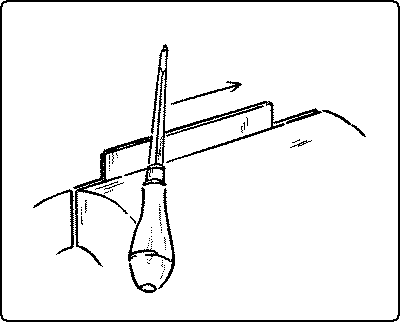

One method of sharpening the scraper is as follows: the scraper is first brought to the desired shape, straight or curved. This may be done either by grinding on the grindstone or by filing with a smooth, flat file, the scraper, while held in a vise. The edge is then carefully draw-filed, i. e., the file, a smooth one, is held (one hand at each end) directly at right angles to the edge of the scraper, Fig. 153, and moved sidewise from end to end of the scraper, until the edge is quite square with the sides. Then the scraper is laid flat on the oilstone and rubbed, first on one side and then on the other till the sides are bright and smooth along the edge, Fig. 154. Then it is set on edge on the stone and rubbed till there are two sharp square corners all along the edge, Fig. 155. Then it is put in the vise again and by means of a burnisher, or scraper steel, both of these corners are carefully turned or bent over so as to form a fine burr. This is done by tipping the scraper steel at a slight angle with the edge and rubbing it firmly along the sharp corner, Fig. 156.

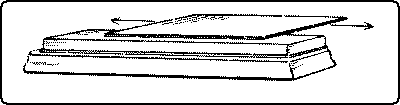

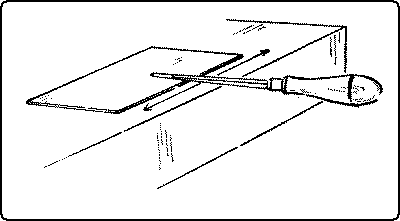

To resharpen the scraper it is not necessary to file it afresh every time, but only to flatten out the edges and turn them again with slightly more bevel. Instead of using the oilstone an easier, tho less perfect, way to flatten out the burr on the edges is to lay the scraper flat on the bench near the edge. The scraper steel is then passed rapidly to and fro on the flat side of the scraper, Fig. 157. After that the edge should be turned as before.

Sandpaper. The “sand” is crushed quartz and is very hard and sharp. Other materials on paper or cloth are also used, as carborundum, emery, and so on. Sandpaper comes in various grades of coarseness from No. 00 (the finest) to No. 3, indicated on the back of each sheet. For ordinary purposes No. 00 and No. 1 are sufficient. Sandpaper sheets may readily be torn by placing the sanded side down, one-half of the sheet projecting over the square edge of the bench. With a quick downward motion the projecting portion easily parts. Or it may be torn straight by laying the sandpaper on a bench, sand side down, holding the teeth of a back-saw along the line to be torn. In this case, the smooth surface of the sandpaper would be against the saw.

Sandpaper should never be used to scrape and scrub work into shape, but only to obtain an extra smoothness. Nor ordinarily should it be used on a piece of wood until all the work with cutting tools is done, for the fine particles of sand remaining in the wood dull the edge of the tool. Sometimes in a piece of cross-grained wood rough places will be discovered by sandpapering. The surface should then be wiped free of sand and scraped before using a cutting tool again. In order to avoid cross scratches, work should be “sanded” with the grain, even if this takes much trouble. For flat surfaces, and to touch off edges, it is best to wrap the sandpaper over a rectangular block of wood, of which the corners are slightly rounded, or it may be fitted over special shapes of wood for specially shaped surfaces. The objection to using the thumb or fingers instead of a block, is that the soft portions of the wood are cut down faster than the hard portions, whereas the use of a block tends to keep the surface even.

Steel wool is made by turning off fine shavings from the edges of a number of thin discs of steel, held together in a lathe. There are various grades of coarseness, from No. 00 to No. 3. Its uses are manifold: as a substitute for sandpaper, especially on curved surfaces, to clean up paint, and to rub down shellac to an “egg-shell” finish. Like sandpaper it should not be used till all the work with cutting tools is done. It can be manipulated until utterly worn out.

Noyes, W. (1910). Chapter IV. WOOD HAND TOOLS. In Handwork in Wood (pp. 83-87). Peoria, Ill.: Manual Arts Press

Learn all about woodworking and more online here at the Heritage School of Woodworking’s Online Woodworking Courses. Try out the Log to Spoon Course: it’s a great intro to ax work and using scrapers. If you want up close and personal views on scraper sharpening, see our Sharpening Card Scraper and Sharpening Cabinet Scraper classes. See our Setting Up Shop blog on the basic tools you need to start out in woodworking.

Tell us what you think!

Comments are closed.